3. Fixed Exchange Rate Systems

Throughout history, governments have attempted to establish stable exchange rate systems to reduce uncertainty in international trade.

Gold standard

One of the earliest examples was the gold standard, which required countries to link the value of their currencies to a fixed amount of gold. This system provided stability by ensuring that currencies had a tangible backing. However, after World War I, many countries abandoned the gold standard due to economic instability and competitive devaluations.

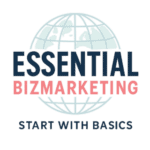

The image illustrates the contrast between the gold standard during peacetime and its collapse due to war financing. On the left side, the gold standard system is depicted, where currency issuance is backed by gold reserves. Under this system, wages are paid in gold-backed currency, and in return, workers provide labor and services. This structure ensures economic stability as the value of money remains linked to a tangible asset, maintaining public trust in the financial system.

On the right side, the breakdown of the gold standard is shown as governments increase currency issuance without maintaining sufficient gold reserves. During wartime, instead of being backed by gold, newly issued money is used to finance military production, leading to an excess supply of currency. This results in inflation as the purchasing power of money declines, and public confidence in the monetary system erodes. The fundamental difference between these two scenarios is that, in peacetime, money maintains its value through convertibility to gold, whereas in wartime, the suspension of gold backing leads to an unstable financial environment driven by excessive money supply and rising prices.

Bretton Woods Agreement

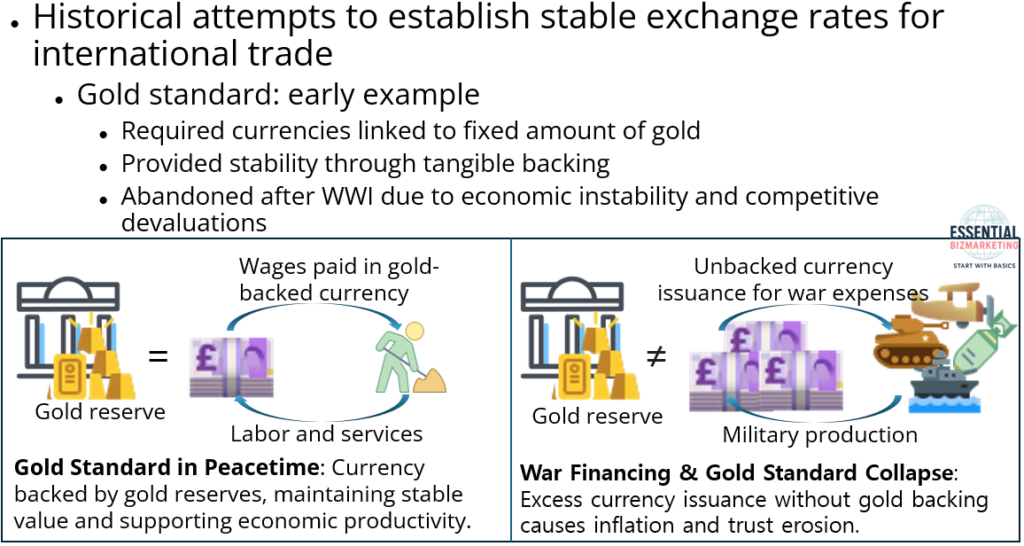

Following the collapse of the gold standard, the Bretton Woods Agreement was established in 1944 to create a new international monetary system. This system tied the value of the U.S. dollar to gold at a fixed rate of $35 per ounce and linked other currencies to the dollar instead of gold. The agreement aimed to maintain exchange rate stability while allowing limited adjustments when necessary.

Under the Bretton Woods system, the U.S. dollar was pegged to gold at $35 per ounce, while other currencies were fixed to the dollar. This arrangement ensured exchange rate stability and facilitated international trade, as nations could convert their reserves into dollars, which were backed by gold. However, adjustments were permitted under specific conditions to correct imbalances in the global economy.

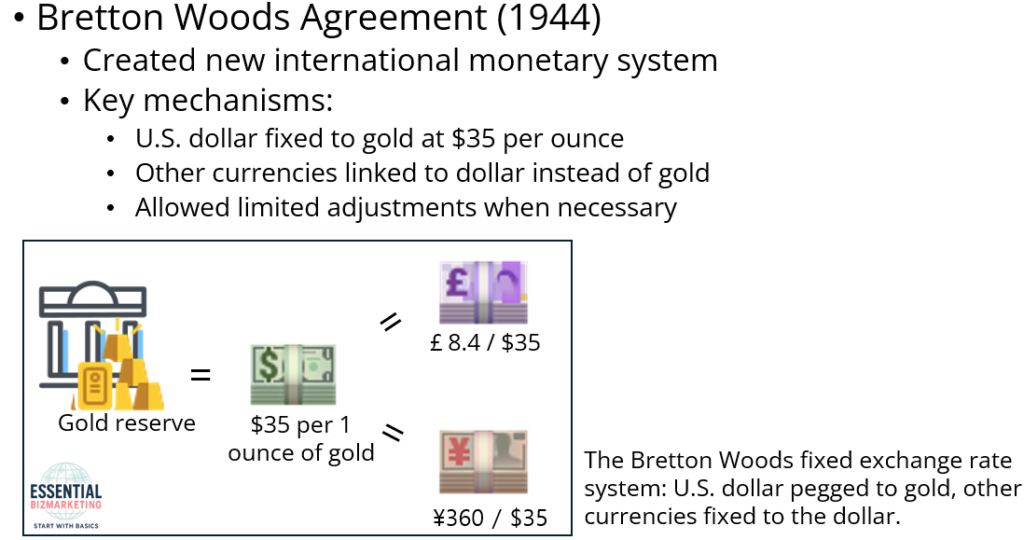

To support this system, two key financial institutions were created: the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which was tasked with regulating exchange rates and providing financial assistance to countries facing balance-of-payment difficulties, and the World Bank, which was established to fund economic development projects.

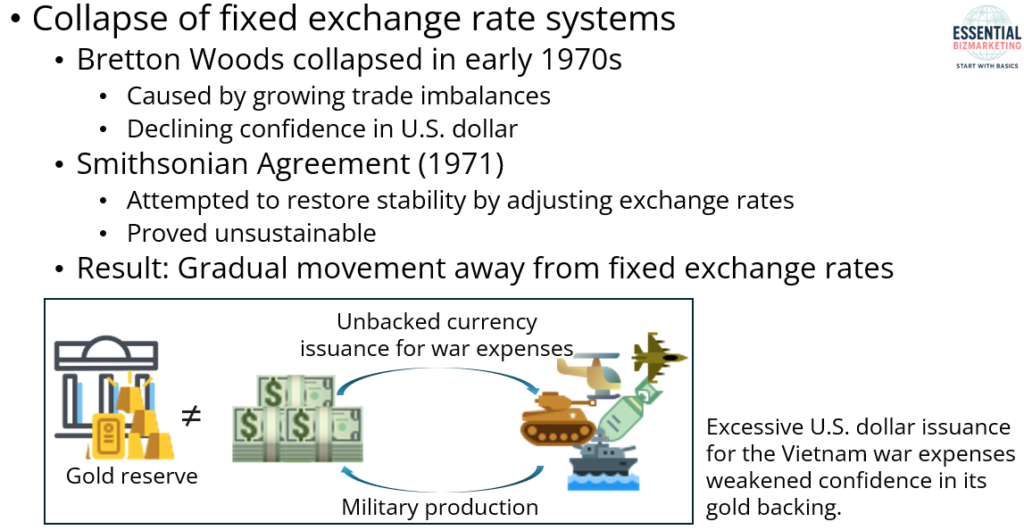

Despite its initial success, the Bretton Woods system collapsed in the early 1970s due to growing trade imbalances and declining confidence in the U.S. dollar. In an attempt to restore stability, the Smithsonian Agreement was signed in 1971, which adjusted the exchange rate system, but it proved to be unsustainable. As a result, countries gradually moved away from fixed exchange rates.

Under the Bretton Woods system, the U.S. dollar was pegged to gold at $35 per ounce. However, extensive spending on the Vietnam War led to the issuance of large amounts of currency without sufficient gold reserves, causing inflation and eroding international trust in the dollar. This imbalance contributed significantly to the collapse of the fixed exchange rate system in the early 1970s.

4. Floating Exchange Rate Systems

After the failure of fixed exchange rate systems, many countries transitioned to floating exchange rates, where market forces such as supply and demand determine currency values. The Jamaica Agreement, signed in 1976, officially recognized floating exchange rates as the new international monetary system. Under this system, governments allow their currencies to fluctuate freely but may intervene in foreign exchange markets to prevent extreme volatility.

Manged Float System

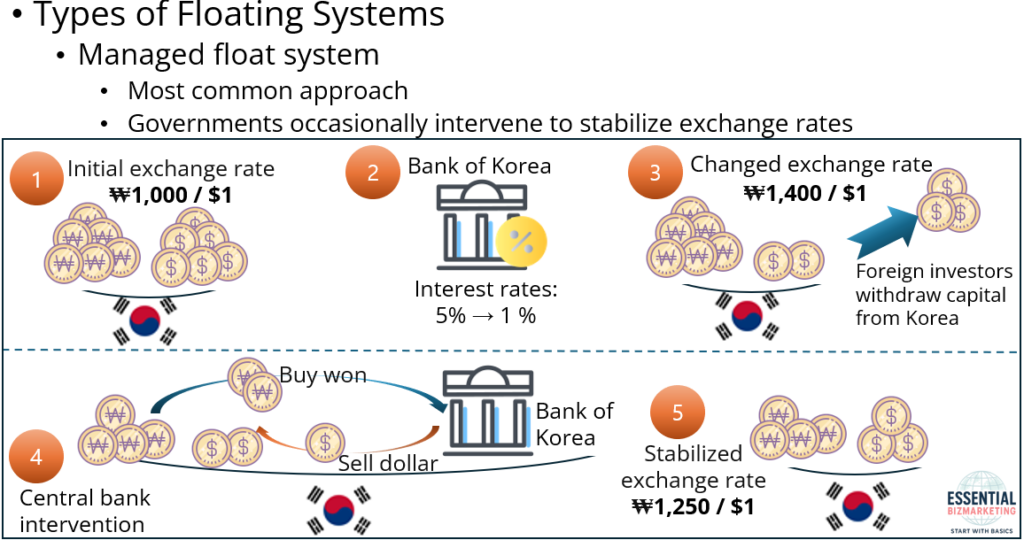

While most countries operate under a managed float system, where governments occasionally intervene to stabilize exchange rates, some nations adopt a pegged exchange rate arrangement.

The illustration demonstrates how a managed float exchange rate system functions, using South Korea as an example. Initially, the exchange rate is stable at 1,000 Korean won per U.S. dollar. The Bank of Korea then lowers interest rates from 5% to 1%, which reduces the attractiveness of Korean assets for foreign investors. This leads to a sudden capital outflow as investors withdraw their funds from Korea, causing a sharp depreciation of the Korean won to 1,400 won per dollar due to increased demand for U.S. dollars.

In response, the Bank of Korea intervenes in the foreign exchange market by selling U.S. dollars from its reserves and purchasing Korean won. This action increases the supply of dollars while reducing the supply of won, helping to mitigate excessive depreciation. As a result, the exchange rate stabilizes at approximately 1,250 won per dollar. This example illustrates how central banks utilize managed float systems to counteract severe exchange rate fluctuations driven by monetary policy changes and investor reactions.

Pegged Exchange Rate Sytem

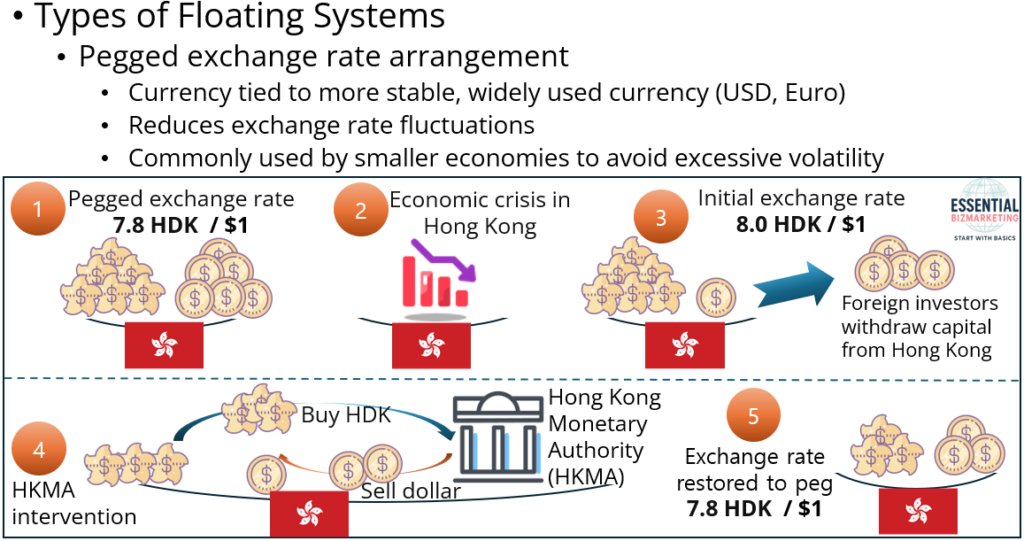

In a pegged system, a country ties its currency to a more stable and widely used currency, such as the U.S. dollar or the euro, to reduce exchange rate fluctuations. This approach is commonly used by smaller economies that seek to avoid excessive currency volatility.

The illustration demonstrates how a pegged exchange rate system functions using Hong Kong as an example. Initially, the Hong Kong dollar (HKD) is pegged to the U.S. dollar at 1 USD = 7.8 HKD. However, an economic crisis in Hong Kong triggers a large capital outflow, as foreign investors sell HKD and move their funds into USD. This increased demand for USD and excess supply of HKD causes the exchange rate to weaken, rising to 8.0 HKD per USD.

To counteract this depreciation, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) intervenes by selling U.S. dollars from its foreign exchange reserves and buying back HKD from the market. This reduces the supply of HKD in circulation and increases its value. As a result, the exchange rate is successfully brought back to its pegged level of 7.8 HKD per USD.

Unlike a managed floating system, where government intervention only aims to reduce excessive fluctuations without fixing the rate, a pegged exchange rate system mandates full restoration to the predetermined rate. In this case, the HKMA ensures that the exchange rate exactly returns to 7.8 HKD per USD, maintaining the stability of the peg.

5. Exchange Rate Stability Challenges: Lessons from Financial Crises

Financial crises have repeatedly demonstrated the challenges of maintaining exchange rate stability.

Mexican Peso Crisis (1994)

The Mexican Peso Crisis in 1994: The Mexican Peso Crisis of 1994-1995 was a currency and financial crisis triggered by a failed exchange rate peg, rapid capital flight, and a depletion of foreign reserves, leading to a sharp peso depreciation, soaring interest rates, and a deep economic recession.

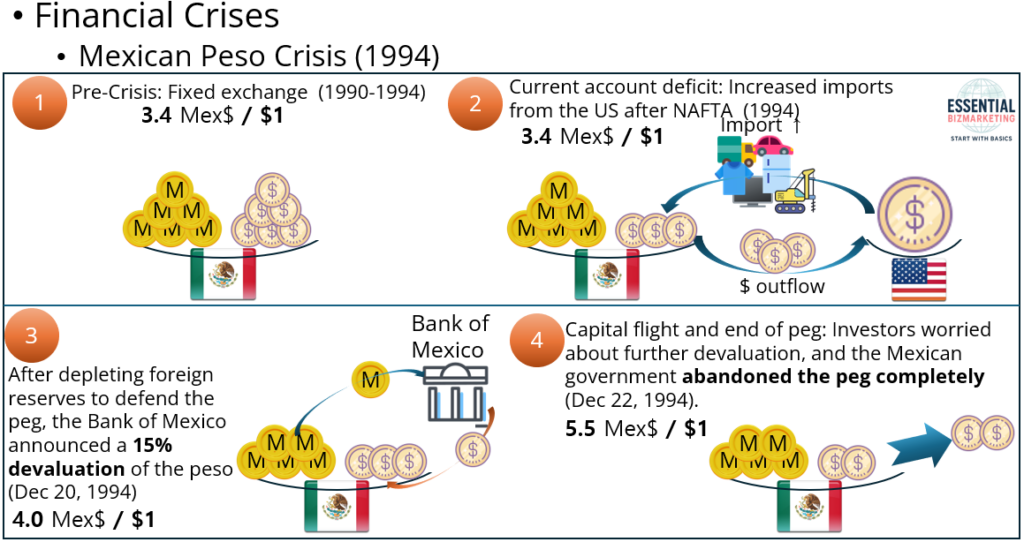

The illustrations depict the sequence of events that led to the Mexican Peso Crisis of 1994-1995, highlighting key economic and financial developments. Before the crisis, Mexico maintained a fixed exchange rate system, pegging the peso at 3.4 Mex$ per USD. However, following the implementation of NAFTA in 1994, Mexico’s imports from the United States surged, leading to a growing current account deficit. Since the country relied on foreign capital inflows to finance this deficit, the Mexican economy became highly vulnerable to investor sentiment.

As concerns over Mexico’s economic stability grew, investors began withdrawing capital, putting pressure on the peso. The Bank of Mexico attempted to defend the peg by using its foreign reserves, but this strategy proved unsustainable as reserves depleted rapidly. On December 20, 1994, the Mexican government was forced to announce a 15% devaluation, setting the new exchange rate at 4.0 Mex$ per USD. Instead of restoring confidence, the move triggered panic among investors, who feared further devaluation and intensified capital flight. Within two days, the government abandoned the peg entirely, allowing the peso to float freely, leading to a sharp depreciation to 5.5 Mex$ per USD.

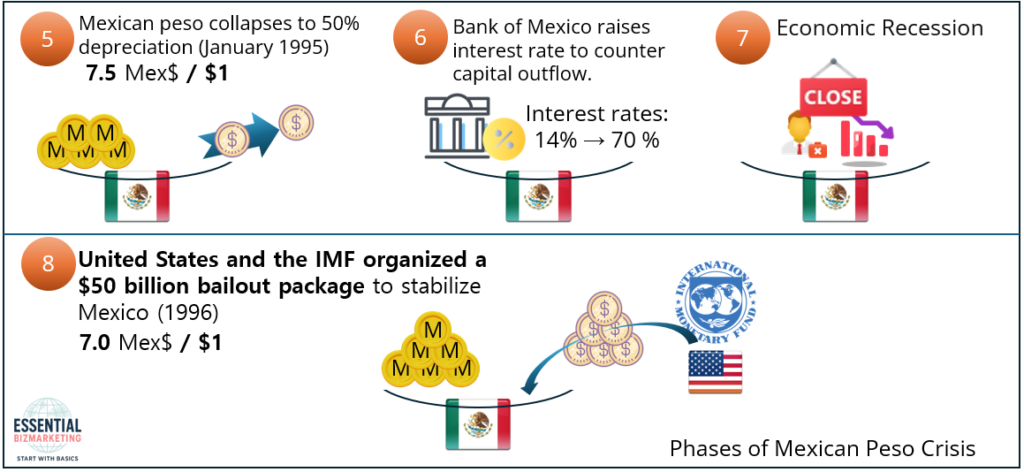

By January 1995, the peso had collapsed further, losing nearly 50% of its value, reaching 7.5 Mex$ per USD. In an effort to stabilize the financial system and restore investor confidence, the Bank of Mexico drastically raised interest rates from 14% to 70%. However, this sharp monetary tightening led to a severe credit crunch, which, in turn, triggered an economic recession, causing widespread business closures and financial distress.

To prevent the crisis from spreading to other emerging markets and to stabilize Mexico’s economy, the United States and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) organized a $50 billion bailout package in 1996. The intervention helped restore confidence, and the exchange rate gradually stabilized at 7.0 Mex$ per USD. The crisis underscored the dangers of maintaining a semi-fixed exchange rate without sufficient foreign reserves, as well as the risks associated with over-reliance on short-term foreign capital to finance economic imbalances.

Asian Financial Crisis (1997)

Asian Financial Crisis (1997): The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis was triggered by excessive foreign borrowing, speculative real estate investments, and fixed exchange rate vulnerabilities. As investors withdrew their dollars, currencies collapsed, forcing governments to abandon pegs and seek IMF bailouts, leading to severe economic contractions and financial reforms.

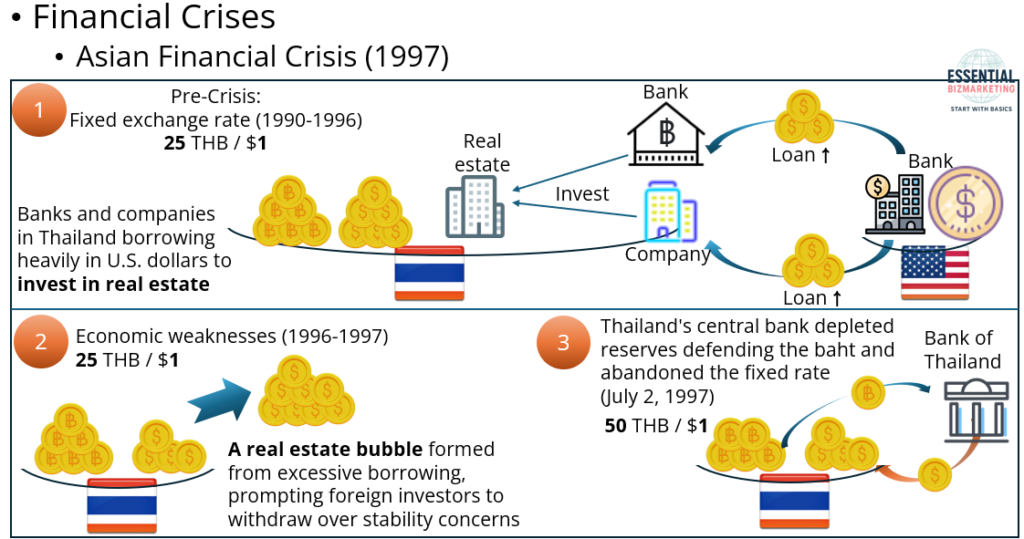

The illustrations depict the key events leading up to the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, focusing on the role of financial imbalances, speculative investments, and foreign capital flows. Before the crisis, many Asian economies, including Thailand, operated under fixed exchange rate systems. From 1990 to 1996, Thailand maintained a fixed exchange rate of 25 Thai baht per U.S. dollar, attracting substantial foreign capital inflows. Banks and companies borrowed heavily in U.S. dollars, using these funds to invest in real estate and speculative ventures. This credit boom fueled a property bubble, with banks providing increasing amounts of loans for real estate projects, assuming that the economic growth would continue.

By 1996-1997, underlying weaknesses in the economy became evident. Thailand’s real estate market became oversaturated, and as concerns about the country’s financial stability grew, foreign investors began pulling out their dollars. This capital flight put downward pressure on the baht, but because the currency was pegged to the U.S. dollar, the Bank of Thailand had to intervene, selling foreign reserves to defend the exchange rate. However, as foreign reserves depleted rapidly, the Thai government was forced to abandon the fixed exchange rate on July 2, 1997. The baht collapsed from 25 to 50 THB/USD, triggering a financial panic across the region.

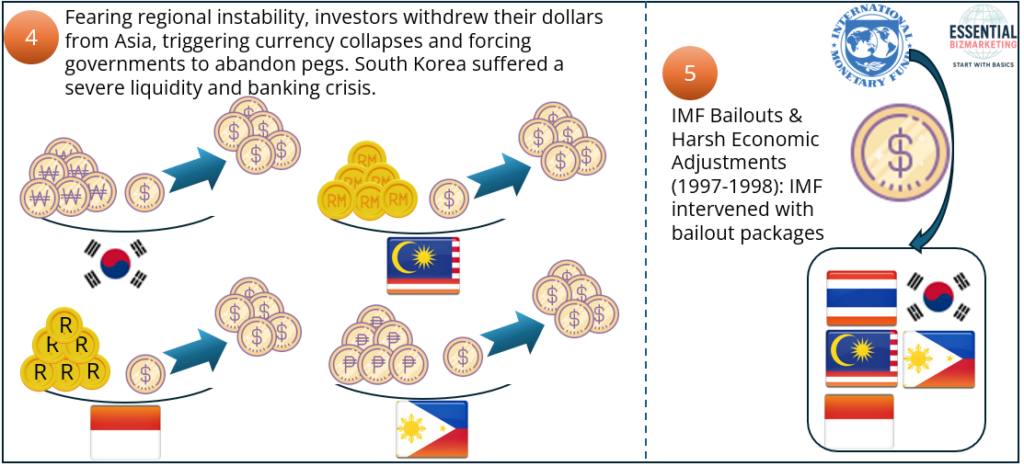

The crisis quickly spread to other Asian economies as investors withdrew their dollar holdings from countries like South Korea, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines. This led to currency collapses, forcing governments to abandon their currency pegs and allow free-floating exchange rates. The sudden loss of capital resulted in banking crises and liquidity shortages, with South Korea being hit particularly hard, facing a systemic banking collapse.

In response, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) intervened with bailout packages for the worst-affected countries, including Thailand, South Korea, and the Philippines. However, these bailouts came with harsh economic adjustments, including austerity measures, high interest rates, and financial sector restructuring. The crisis underscored the dangers of excessive reliance on foreign-denominated debt, speculative investments, and unsustainable fixed exchange rate policies, leading to significant economic and financial reforms in many Asian economies in the years that followed.

All financial crises mentioned above highlighted the risks associated with sudden capital outflows and exchange rate mismanagement. These crises underscored the need for strong financial regulations, investor confidence, and sound monetary policies to ensure stability in the international monetary system.

6. Conclusion: Future of the International Monetary System

The international monetary system continues to evolve as countries adapt to changing economic conditions. Some governments advocate for greater intervention to stabilize exchange rates, while others prefer a more market-driven approach with minimal interference. The IMF remains a central institution in managing financial stability, yet its role has been the subject of debate, with critics arguing that it should undergo reforms to better address the complexities of the modern global economy.

Given the growing interconnectedness of financial markets, businesses and governments must closely monitor exchange rate movements, inflation trends, and interest rate policies. The ability to anticipate and respond to these economic factors is crucial for maintaining financial stability and ensuring sustainable growth in an increasingly globalized economy.

Related videos

- Trade and currency

- How the US-China trade war turned into a currency war

- International Monetary System

- Financial Crises and Currency Shocks

- Forex Market Instruments & Institutions

- Role of the IMF and World Bank

- Case Studies – Companies and Exchange Rate Fluctuations

- Monetary policy

📚 References

Wild, J. J., & Wild, K. L. (2019). International business: The challenges of globalization (9th ed.). Pearson.

📁 Start exploring the Blog

📘 Or learn more About this site

🧵 Or follow along on X (Twitter)

🔎 Looking for sharp perspectives on global trade and markets?

I recommend @GONOGO_Korea as a resource I trust and regularly learn from.