Case study

Walmart’s international expansion exemplifies the growth of global trade and economic interdependence. Starting with a single store in Mexico in 1991, Walmart now operates approximately 11,500 stores worldwide, with over 6,200 stores across 27 countries outside the US. As one of the world’s largest companies with nearly $486 billion in global sales, Walmart has significantly influenced international trade patterns, particularly with China. By sourcing low-cost merchandise from manufacturing hubs like China, Walmart has contributed to increasing Chinese imports to the US, to the extent that if Walmart were a country, it would be China’s sixth-largest trading partner.

China’s emergence as “the world’s factory” has led to trade growth two to three times faster than the global average. About 18% of Japan’s imports and 12% of US imports come from China, while China imports various goods from the US, including construction materials and medical equipment. This bilateral trade demonstrates increasing global economic interdependence, as Western consumer goods companies like Walmart expand into the Chinese market.

International trade allows consumers worldwide to experience other cultures through imported goods, from French perfumes to Japanese porcelain and American jeans, illustrating how trade patterns reflect and influence cultural exchanges alongside economic relationships.

1. Benefits, Volume, and Patterns of International Trade

International trade involves the exchange of goods and services across national borders. It allows countries to access products they cannot produce domestically, provides consumers with more choices, and generates employment. Trade is a crucial factor in economic interdependence among nations. The total value of global trade is significant, with merchandise exports reaching $16.5 trillion and service exports valued at $4.8 trillion. Wealthier nations account for about 60 percent of world trade, while trade between high-income and lower-income countries makes up approximately 34 percent. A relatively small portion of global trade occurs exclusively between lower-income nations.

Trade dependency can be beneficial, particularly for developing countries that rely on wealthier nations for economic growth. However, excessive dependence on a single trade partner can be risky, as economic downturns or political instability in one country can negatively impact its trade-dependent partners. This has been observed in regions such as Central and Eastern Europe, where trade with Germany has significantly shaped economic outcomes. While globalization fosters trade interdependence, it also exposes countries to vulnerabilities associated with economic fluctuations.

2. Mercantilism

Mercantilism was a dominant economic theory from the 1500s to the late 1700s. It promoted the idea that a nation’s wealth was measured by its stockpile of gold and silver. Under this system, governments sought to maintain a trade surplus by encouraging exports and restricting imports. This was achieved through various means, including imposing tariffs on imports, providing subsidies to domestic industries, and controlling colonies to secure cheap raw materials and guaranteed markets for finished goods.

Despite its widespread adoption, mercantilism had inherent flaws. It was based on the assumption that world wealth was fixed and that one country’s gain came at another’s expense, a concept known as the zero-sum game. However, modern trade theories demonstrate that trade benefits all participating nations. Additionally, mercantilist policies hindered the economic development of colonies by restricting their ability to sell goods at fair market prices and limiting their purchasing power for imported products. Over time, as global trade expanded, the inefficiencies of mercantilism became apparent, leading to the development of more advanced trade theories.

3. Theories of Absolute and Comparative Advantage

Absolute Advantage

Adam Smith introduced the theory of absolute advantage in 1776, arguing that countries should produce goods in which they have the highest efficiency and trade for products that others can produce more efficiently. A country has an absolute advantage when it can produce a good using fewer resources than another country. Smith opposed trade restrictions and emphasized the benefits of free trade based on specialization.

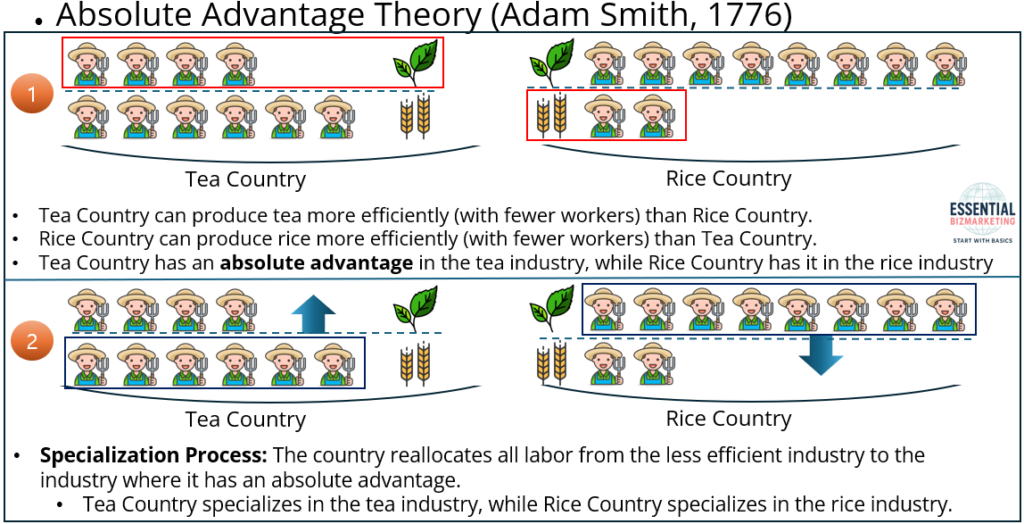

There are two countries (Tea Country and Rice Country) and they produce tea and rice. In Tea Country, it takes 4 workers to produce 1 unit of tea and 6 workers to produce 1 unit of rice. In Rice Country, it takes 8 workers to produce 1 unit of tea and 2 workers to produce 1 unit of rice.

Now, let’s look at which country has an absolute advantage in which industry. For the tea industry, Tea Country needs fewer workers (4) than Rice Country does (8). Therefore, Tea Country has an absolute advantage in the tea industry. For the rice industry, Rice Country needs fewer workers (2) than Tea Country does (6). Thus, Rice Country has an absolute advantage in the rice industry.

As Tea Country has an absolute advantage in the tea industry, it decided to specialize in the tea industry by pulling out all workers from the rice industry and allocating them to the tea industry. Meanwhile, as Rice Country has an absolute advantage in the rice industry, it decided to specialize in the rice industry by pulling out all workers from the tea industry and allocating them to the rice industry.

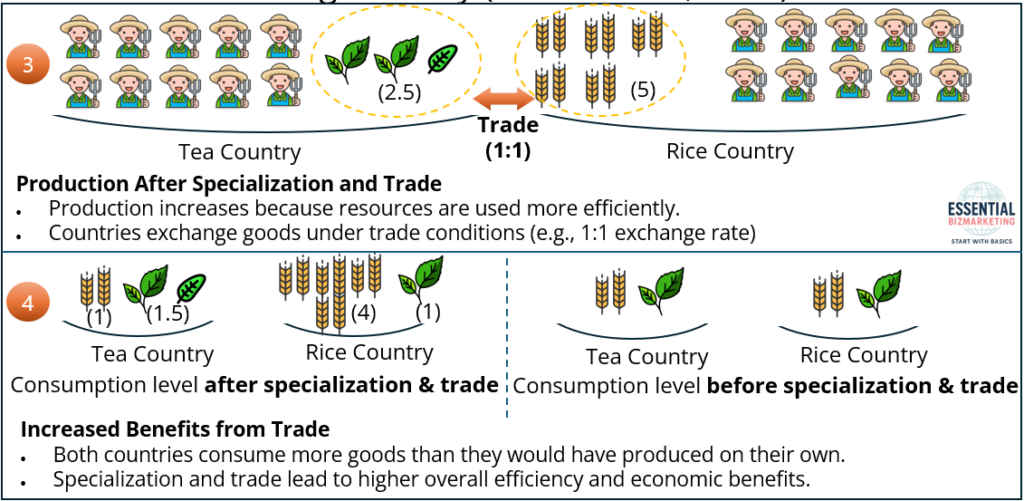

After specialization, Tea Country has all 10 workers in the tea industry so it can produce 2.5 units of tea, considering it needs 4 workers to produce 1 unit of tea. Rice Country has all 10 workers in the rice industry, so it can produce 5 units of rice, considering it needs 2 workers to produce 1 unit of rice. Then, the two countries start trading products under a 1:1 trade condition.

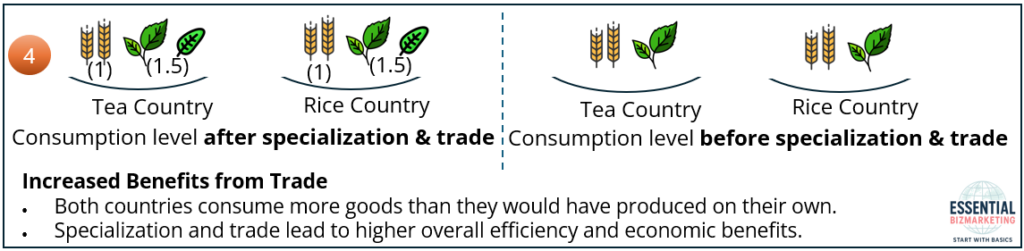

Under a 1:1 trade condition, Tea Country can consume 1.5 units of tea and 1 unit of rice while Rice Country can consume 1 unit of tea and 4 units of rice. Since both countries were only able to consume 1 unit of tea and 1 unit of rice before specialization and trade, both countries are now able to consume more products after specialization and trade.

Comparative Advantage

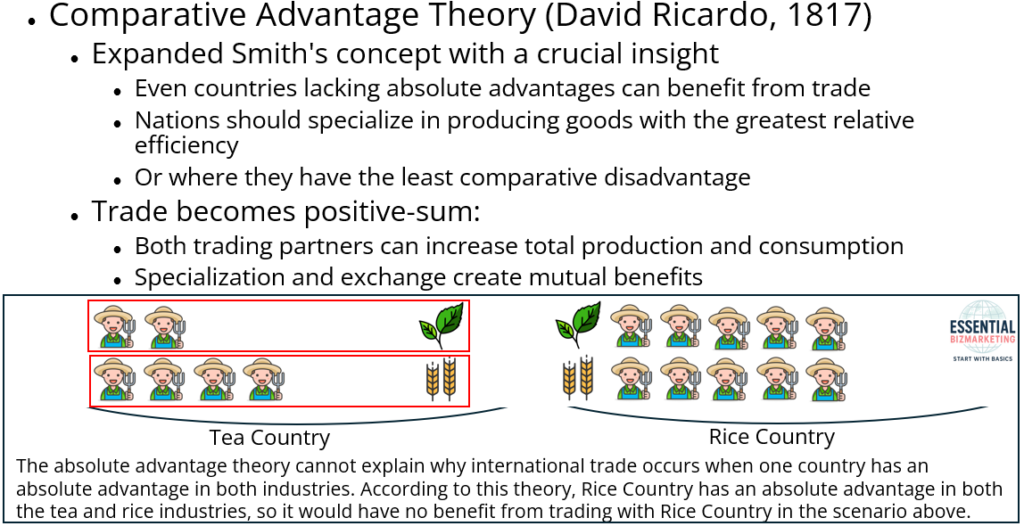

David Ricardo expanded this idea in 1817 with the theory of comparative advantage. He demonstrated that even if a country has an absolute advantage in producing multiple goods, it should specialize in the one it produces most efficiently relative to others. The other country, even if less efficient overall, can still benefit by specializing in the good where it has the least disadvantage. This concept highlights that trade is a positive-sum game, meaning both nations can achieve higher total production and consumption through specialization and exchange.

There are two countries (Tea Country and Rice Country) and they produce tea and rice. In Tea Country, it takes 2 workers to produce 1 unit of tea and 4 workers to produce 1 unit of rice. In Rice Country, it takes 5 workers to produce 1 unit of tea and 5 workers to produce 1 unit of rice.

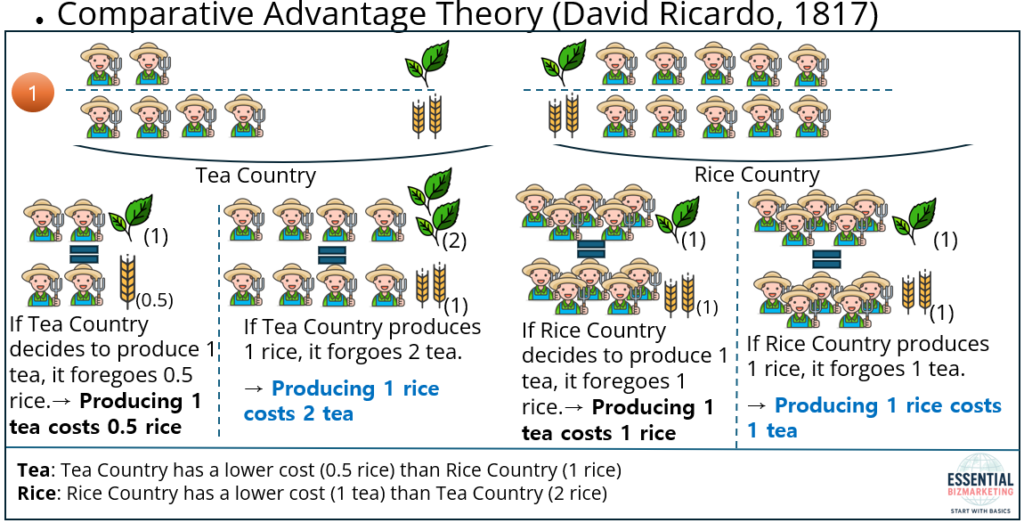

In Tea Country, 2 workers can produce 1 unit of tea but only 0.5 units of rice. Therefore, if Tea Country decides to produce 1 unit of tea, it must give up 0.5 units of rice. Meanwhile, 4 workers can produce 1 unit of rice but as many as 2 units of tea. Therefore, if Tea Country decides to produce 1 unit of rice, it must give up as many as 2 units of tea.

In Rice Country, 5 workers can produce 1 unit of tea and 1 unit of rice. Therefore, if Rice Country decides to produce 1 unit of tea, it must give up 1 unit of rice. Meanwhile, 5 workers can produce 1 unit of rice and 1 unit of rice. Therefore, if Rice Country decides to produce 1 unit of rice, it must give up 1 unit of tea.

Now, let’s examine which country has a comparative advantage in which industry. For the tea industry, to produce 1 unit of tea, Tea Country only needs to give up 0.5 rice but Rice Country should give up 1 rice. Therefore, Tea Country has a lower opportunity cost (0.5 rice) than Rice Country (1 rice) and has a comparative advantage in the tea industry.

For the rice industry, to produce 1 unit of rice, Tea Country needs to give up 2 tea but Rice Country only needs to give up 1 tea. Therefore, Rice Country has a lower opportunity cost (1 tea) than Tea Country (2 tea) and has a comparative advantage in the tea industry.

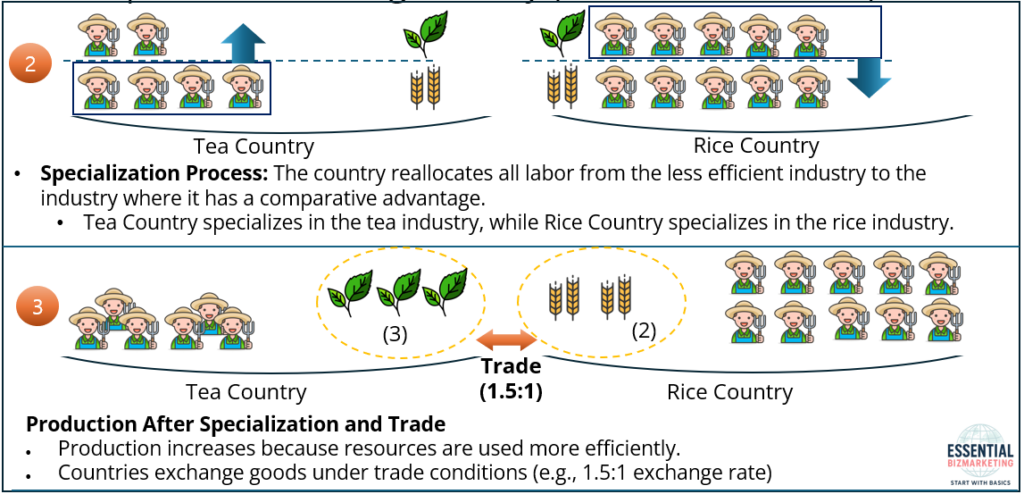

As Tea Country has a comparative advantage in the tea industry, it decided to specialize in the tea industry by pulling out all workers from the rice industry and allocating them to the tea industry. Meanwhile, as Rice Country has a comparative advantage in the rice industry, it decided to specialize in the rice industry by pulling out all workers from the tea industry and allocating them to the rice industry.

After specialization, Tea Country has all 6 workers in the tea industry so it can produce 3 units of tea, considering it needs 2 workers to produce 1 unit of tea. Rice Country has all 10 workers in the rice industry, so it can produce 2 units of rice, considering it needs 5 workers to produce 1 unit of rice. Then, the two countries start trading products under a 1.5:1 (Tea : Rice) trade condition.

Under a 1.5:1 trade condition, both countries can consume 1.5 units of tea and 1 unit of rice. Since both countries were only able to consume 1 unit of tea and 1 unit of rice before specialization and trade, both countries are now able to consume more products after specialization and trade.

While absolute and comparative advantage theories provide strong arguments for free trade, they are based on several assumptions, including the absence of transportation costs, full mobility of resources within nations, and no changes in efficiency over time. In reality, factors such as government policies, labor mobility, and technological progress influence trade dynamics.

4. Factor Proportions Theory

The factor proportions theory, developed by Eli Heckscher and Bertil Ohlin, focuses on the relationship between a country’s resource endowments and its trade patterns. It argues that countries will export goods that require abundant resources and import goods that require scarce resources. For example, a country with a large labor force and low wages will specialize in labor-intensive goods, while a capital-rich country will focus on capital-intensive industries.

However, empirical studies have challenged this theory. The Leontief Paradox, discovered by economist Wassily Leontief in the 1950s, found that the United States, despite being capital-abundant, exported more labor-intensive goods and imported capital-intensive products.

This contradiction suggests that factors beyond simple resource availability, such as technology and workforce skills, play a crucial role in determining trade patterns. Although the factor proportions theory provides a foundational understanding of trade, real-world data indicate that trade flows are influenced by multiple factors beyond resource endowments.

5. International Product Life Cycle Theory

Raymond Vernon developed the international product life cycle theory in the 1960s to explain how new products evolve in the global market. The theory outlines three stages: the new product stage, the maturing product stage, and the standardized product stage. Initially, new products are developed and produced in high-income countries where demand and purchasing power are strong. As demand grows, production expands to other developed nations, and eventually, manufacturing shifts to lower-cost developing countries.

Over time, the original innovating country may transition from being an exporter to an importer of the product, as production becomes more cost-effective elsewhere. This shift reflects the changing competitive dynamics in global markets.

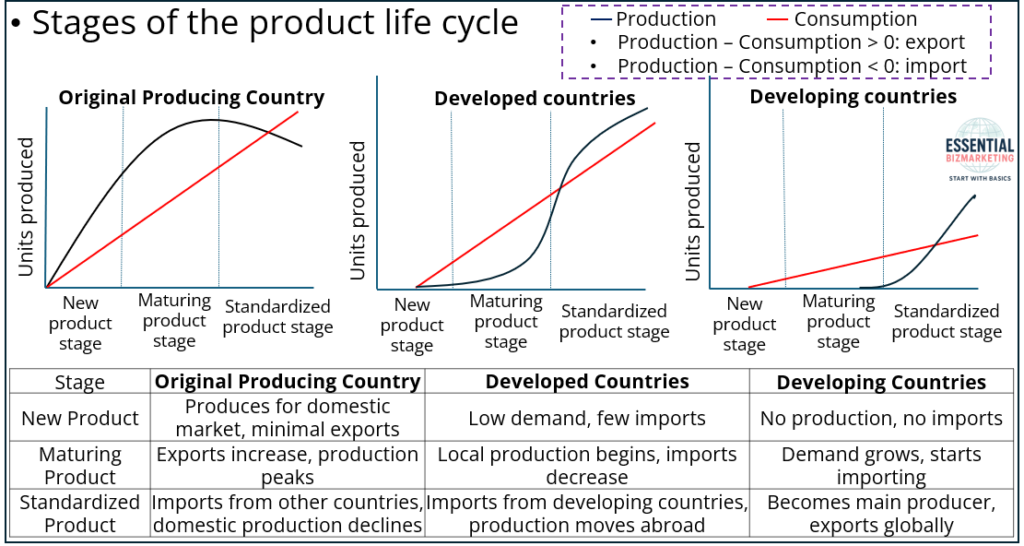

The International Product Life Cycle (IPLC) Theory explains how the production and consumption patterns of a product evolve over time across different types of economies. The theory categorizes countries into three groups: the original producing country (typically an industrialized and innovative nation), other developed countries (advanced economies that adopt the product after its introduction), and developing countries (emerging markets that eventually become major producers). The product moves through three stages—new product, maturing product, and standardized product—which dictate where it is produced and how trade patterns shift.

In the new product stage, the product is first developed and introduced in the original producing country, where demand is initially driven by high purchasing power and advanced consumer needs. At this stage, production is kept within the innovating country to remain close to research and development efforts and to quickly adapt to market feedback. Since the product is new, exports are minimal, and international demand is relatively low. Other developed countries show little interest in the product at this point, leading to limited imports. In developing countries, there is neither significant demand nor production capacity for the product.

As the product enters the maturing product stage, awareness and demand rise both in the innovating country and internationally. Exports from the original producing country increase as international markets begin to recognize the product’s benefits. Over time, production facilities are established in developed countries with high demand, reducing the need for imports from the innovating country. Meanwhile, developing nations start importing the product as it gains popularity, though they have not yet begun local production. This stage is characterized by rising exports from the innovating country and the gradual shift of production to developed nations.

In the standardized product stage, competition intensifies, leading to price sensitivity in the market. Companies respond by seeking cost-effective manufacturing solutions, often relocating production to developing countries where labor and production costs are lower. At this point, the original producing country sees a decline in domestic production and begins importing the product from other nations. Developed countries also shift production abroad, relying more on imports from developing countries. Eventually, developing nations become the dominant manufacturers and start exporting the product globally, including to the original innovating country and other industrialized markets.

The accompanying diagram visually represents these stages by plotting production and consumption trends in each country type. The black production curve and red consumption line indicate whether a country is an exporter or importer at different stages of the product life cycle. When production exceeds consumption, the country is an exporter; when consumption surpasses production, it becomes an importer. This trade dynamic highlights the shifting patterns of global production and the strategic movement of industries in pursuit of cost efficiency and market expansion.

However, the rapid advancement of technology and globalization has reduced the time frame of this cycle. Companies now introduce products in multiple markets simultaneously, and production is often dispersed across multiple countries from the outset. As a result, the product life cycle theory has become less applicable to modern trade patterns.

6. New Trade Theory and First-Mover Advantage

New trade theory, developed in the 1970s and 1980s, provides additional insights into trade patterns. It argues that economies of scale play a critical role in international trade. As firms specialize and expand production, they achieve lower costs per unit, making them more competitive in global markets. This creates an advantage for large firms that can dominate industries and establish barriers to entry for smaller competitors.

The theory also highlights the significance of first-mover advantage. Companies that enter a market early can establish strong brand recognition, secure key resources, and develop customer loyalty before competitors arrive. This advantage can be reinforced by government support, particularly in industries where research and development require substantial investment. The new trade theory suggests that trade success is not solely determined by resource availability but also by market dynamics and firm-level strategies.

7. National Competitive Advantage and Porter’s Diamond

Michael Porter’s national competitive advantage theory explains why certain countries excel in specific industries. According to Porter, four key factors shape national competitiveness: factor conditions, demand conditions, related and supporting industries, and firm strategy, structure, and rivalry.

Factor conditions include both basic resources, such as land and labor, and advanced resources, such as skilled labor and technology. Demand conditions refer to the level of domestic consumer sophistication, which drives companies to innovate and improve product quality.

Related and supporting industries contribute to a nation’s competitiveness by forming clusters that enhance efficiency and knowledge sharing. Firm strategy and competition also play a vital role, as intense rivalry among domestic firms encourages continuous improvement.

Porter also considers the influence of government policies and chance events. Governments can shape national competitiveness by investing in infrastructure, education, and technology. Meanwhile, unexpected events, such as economic crises or technological breakthroughs, can either strengthen or weaken a country’s position in global markets. Porter’s model provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the factors that contribute to a nation’s trade success.

8.Conclusion

International trade theories have evolved from mercantilism to modern frameworks that emphasize specialization, comparative advantage, economies of scale, and national competitiveness. While early theories focused on resource availability, contemporary approaches recognize the role of firm strategies, government policies, and global market dynamics. Trade remains a vital driver of economic growth, and nations benefit most when they leverage their unique strengths and participate in global markets.

📚 References

Wild, J. J., & Wild, K. L. (2019). International business: The challenges of globalization (9th ed.). Pearson.

📁 Start exploring the Blog

📘 Or learn more About this site

🧵 Or follow along on X (Twitter)

🔎 Looking for sharp perspectives on global trade and markets?

I recommend @GONOGO_Korea as a resource I trust and regularly learn from.