Overview

CJ CheilJedang’s global expansion of Bibigo Mandu illustrates how multinational firms tailor entry modes to the specific characteristics of each target market. Drawing from Chapter 13’s entry mode theories and detailed findings from Practice 2-1, 3, and 4, this analysis highlights the causal links between local market conditions and Bibigo’s chosen strategies—moving beyond surface-level correlations to demonstrate how entry modes were determined because of cultural, economic, and regulatory drivers.

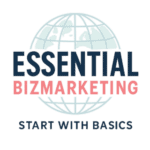

United States: From Exporting to Subsidiary Ownership – A Shift Driven by Market Maturity and Brand Demand

Bibigo initially entered the U.S. through exporting, which is common when companies seek low-risk international experience. As explained in Chapter 13, firms often begin with exporting to test demand, especially in high-income markets.

Practice 4 confirms that the U.S. has the highest per capita income, advanced logistics, and the largest retail market—factors that reduce uncertainty and facilitate initial exports.

Practice 2-1 shows that American consumers favor convenience, individual meals, and premium experiences. Bibigo’s dumplings fit these needs and gained strong traction.

As brand recognition and demand grew, Bibigo strategically escalated its market commitment by acquiring local operations and establishing subsidiaries. This decision was caused by the need for greater control over branding, quality, and distribution—a textbook rationale for transitioning from exporting to ownership-based investment modes, as described in Chapter 13’s stages of internationalization.

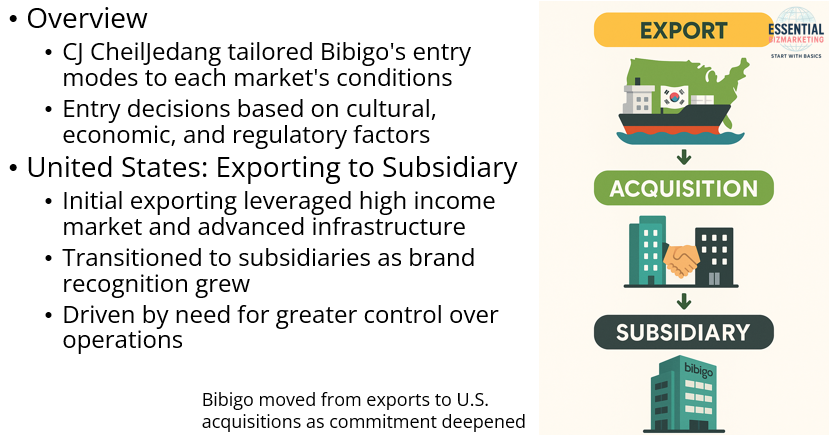

China: Local Production via Joint Ventures – Responding to Low Import Dependency and Cultural Embeddedness

In China, Bibigo avoided exporting as a primary strategy, despite growing consumer interest in Korean cuisine. This decision stems from two critical barriers:

First, Practice 4 identifies China’s low food import dependency (10%), indicating that foreign brands must localize to compete with dominant domestic players.

Second, Practice 2-1 emphasizes that dumplings hold deep cultural value as a shared family food. Bibigo’s ability to enter depended on cultural authenticity and localized production to gain consumer trust.

Given these realities, Bibigo opted for joint ventures and local production, which align with Chapter 13’s description of investment modes that allow for local adaptation while sharing risk. This approach enabled cost efficiency, cultural credibility, and regulatory compliance.

Japan: OEM Partnerships to Overcome Brand Skepticism in a High-Risk Environment

Japan presents a complex market characterized by high uncertainty avoidance and strong brand loyalty, per Hofstede dimensions cited in Practice 2-1.

Practice 4 adds that although logistics are excellent and the retail market is well-developed, high labor costs make direct manufacturing unattractive.

Trust is essential in Japan. New foreign brands face skepticism, especially in the frozen food sector where domestic brands like Ajinomoto dominate.

As a result, Bibigo used OEM partnerships and retail collaborations—a form of contractual entry mode that aligns with Chapter 13’s recommendation to mitigate risk in high-barrier markets. This strategy allowed Bibigo to enter quietly, gain shelf space, and build brand awareness without risking capital-intensive investment.

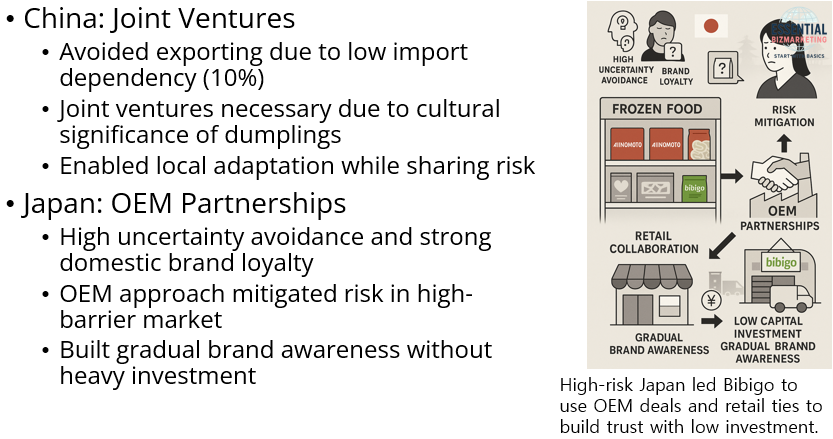

European Union: Wholly Owned Subsidiary in Hungary – A Deliberate Trade-Off Between Stability and Cost Efficiency

The EU offers a stable but costly production environment. While Practice 3 shows that Poland offers better legal protections and fiscal stability, Bibigo ultimately chose Hungary, as explained by:

Lower corporate taxes (9%), greater labor market flexibility, and attractive investment incentives, all of which are outlined in Practice 3.

Practice 4 further supports this choice by noting Hungary’s strategic location, excellent logistics, and lower labor costs compared to the Western EU average.

This decision reflects a deliberate move toward full control via a wholly owned subsidiary, in line with Chapter 13’s investment entry mode. The cause of this choice was cost-minimization and operational flexibility, not institutional superiority.

Southeast Asia: Exporting Supported by Cultural Openness and Economic Constraints

Markets like Vietnam and Indonesia offered opportunities for entry, but their low income levels and underdeveloped infrastructure, as shown in Practice 4, made investment risky.

However, Practice 2-1 highlights low uncertainty avoidance and high collectivism, which supports acceptance of bold foreign flavors and social meal formats.

Therefore, Bibigo chose exporting with local retail partnerships, which keeps costs low while enabling access to culturally receptive consumers. This aligns with Chapter 13’s principle: when infrastructure is weak but cultural acceptance is high, low-commitment modes like exporting are optimal.

Conclusion: A Theory-Grounded, Evidence-Based Entry Mode Strategy

Bibigo’s expansion illustrates the importance of matching entry modes with local conditions—not just in theory but in actual operational decisions. Drawing from Chapter 13, we observe the following causal logic across markets:

- High demand + strong brand → Ownership-based entry (U.S.)

- Cultural embeddedness + low import openness → Joint ventures (China)

- Brand skepticism + high cost → Contractual partnerships (Japan)

- Cost advantage + regional logistics → Wholly owned subsidiary (Hungary)

- Low income + openness to novelty → Exporting (Vietnam/SEA)

Bibigo’s market entries are not arbitrary; they are strategically grounded in institutional economics, cultural adaptation theory, and operational logistics, as validated by the data in the Practice cases.

📚 References

CJ CheilJedang. (2023, March 10). CJ CheilJedang completes construction of factory in Kizuna, Vietnam: Building an outpost for Korean food export. CJ Newsroom. https://newsroom.cj.net/cj-cheiljedang-completes-construction-of-a-factory-in-kizuna-vietnam-building-an-outpost-to-enter-the-global-market-for-korean-food/

CJ Group. (2024, April 5). CJ Group chairman visits Japan to strengthen local partnerships. CJ Newsroom. https://newsroom.cj.net/cj-group-chairman-visits-japan-for-global-expansion/

Dunning, J. H. (1988). The eclectic paradigm of international production: A restatement and some possible extensions. Journal of International Business Studies, 19(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490372

Hwang, J. Y. (2024, November 21). CJ CheilJedang to spur overseas growth with new Hungary, US plants. The Korea Herald. https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20241121050054

Kang, J. (2023, July 31). CJ CheilJedang exits Chinese firm to focus on Korean food in China. The Korea Herald. https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20230731000636

Kim, S. (2025, April 9). CJ Group chair meets Japanese business leaders on first overseas business trip this year. Korea JoongAng Daily. https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/news/2025-04-09/business/industry/CJ-Group-chair-meets-Japanese-business-leaders-on-first-overseas-business-trip-this-year/2281283

Lee, J. (2023, July 31). CJ CheilJedang sells stake in Jixiangju to focus on Bibigo in China. Korea JoongAng Daily. https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2023/07/31/business/industry/Korea-CJ-Cheiljedang-China/20230731165754874.html

Rugman, A. M., & Verbeke, A. (2001). Location, competitiveness, and the multinational enterprise. In A. M. Rugman & T. L. Brewer (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of International Business (pp. 150–177). Oxford University Press.

📁 Start exploring the Blog

📘 Or learn more About this site

🧵 Or follow along on X (Twitter)

🔎 Looking for sharp perspectives on global trade and markets?

I recommend @GONOGO_Korea as a resource I trust and regularly learn from.