The Euro’s Impact on Europe’s Economy

The euro, introduced as Europe’s single currency, has significantly impacted the continent’s economy. Initially, it traded at parity with the US dollar before rising to $1.57, reflecting confidence in the eurozone’s growth. However, the global credit crisis and economic downturn revealed weaknesses in heavily indebted European economies, leading to a decline in the euro’s value to around $1.10 by 2017. Despite this volatility, financial markets stabilized, and the euro’s future remained promising, with analysts predicting it would reach $1.18. The euro provides long-term advantages for European businesses by eliminating exchange-rate risks, improving financial planning, and enhancing competitiveness through mergers and economies of scale. A weaker euro benefits European exporters by making their goods more affordable in global markets, potentially helping companies regain lost market share.

1. Importance of Exchange Rates in Business

Exchange rates play a crucial role in international business because they determine the value of goods and services traded across countries. When a country’s currency is weak, meaning its value is lower relative to other currencies, the price of its exports decreases, making them more attractive to foreign buyers. Conversely, a strong currency makes imports more affordable but reduces the competitiveness of exports. Businesses can take advantage of exchange rate differences by sourcing raw materials from countries with weaker currencies and selling products in markets with stronger currencies.

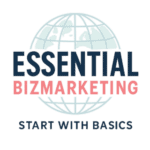

This image illustrates the impact of exchange rates on international trade, focusing on how currency fluctuations affect export and import competitiveness.

Initially, on January 1st, when the exchange rate is ₩1,200 per $1, both the Hyundai Elantra (₩36M) and Chevrolet Malibu ($30,000) are priced equally in U.S. dollars, resulting in a balanced trade scenario.

By February 1st, the exchange rate changes to ₩1,500 per $1, meaning the Korean Won has weakened relative to the U.S. dollar. As a result, the Hyundai Elantra remains ₩36M in Korea but is now only $20,000 in the U.S., making it significantly cheaper than the Chevrolet Malibu, which still costs $30,000. This price advantage increases demand for Korean exports, leading to higher Korean car sales in the U.S. Conversely, American cars become more expensive in Korea, potentially reducing U.S. exports.

This demonstrates how a weaker currency makes exports cheaper and more competitive in foreign markets, boosting trade, whereas a stronger currency makes imports more affordable but reduces export competitiveness.

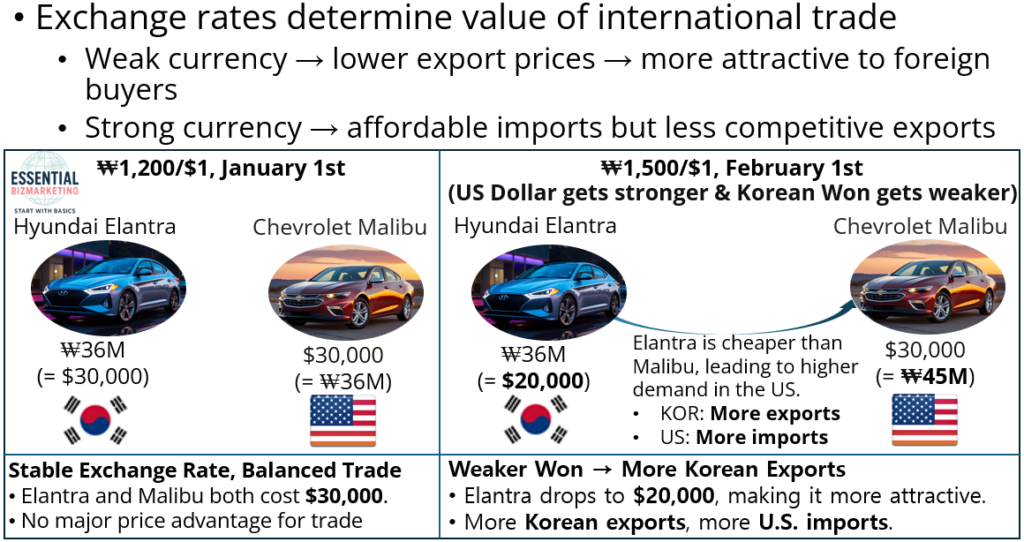

However, fluctuations in exchange rates can significantly impact a company’s profitability. A company that earns revenue in a weak foreign currency but reports its financial statements in a stronger home currency may see its earnings decline when converting the profits.

This image illustrates how exchange rate fluctuations impact business profitability, particularly when converting revenue from a weaker foreign currency to a stronger home currency. The scenario focuses on Tesla selling cars in Japan and converting its earnings from Japanese yen (¥) to U.S. dollars ($). On January 1st, when the exchange rate is ¥100 per $1, Tesla generates ¥6,000,000 in sales. When converted at this rate, the revenue amounts to $60,000, providing a strong return in U.S. dollars.

However, when the Japanese yen weakens and the exchange rate shifts to ¥150 per $1, Tesla still earns the same ¥6,000,000 in Japan, but when converted, it results in only $40,000. Despite stable sales, Tesla experiences a decline in earnings due to the unfavorable exchange rate. This demonstrates how businesses operating in multiple currencies can face financial risks when foreign revenues are converted into a stronger home currency, reducing profitability and affecting overall financial performance.

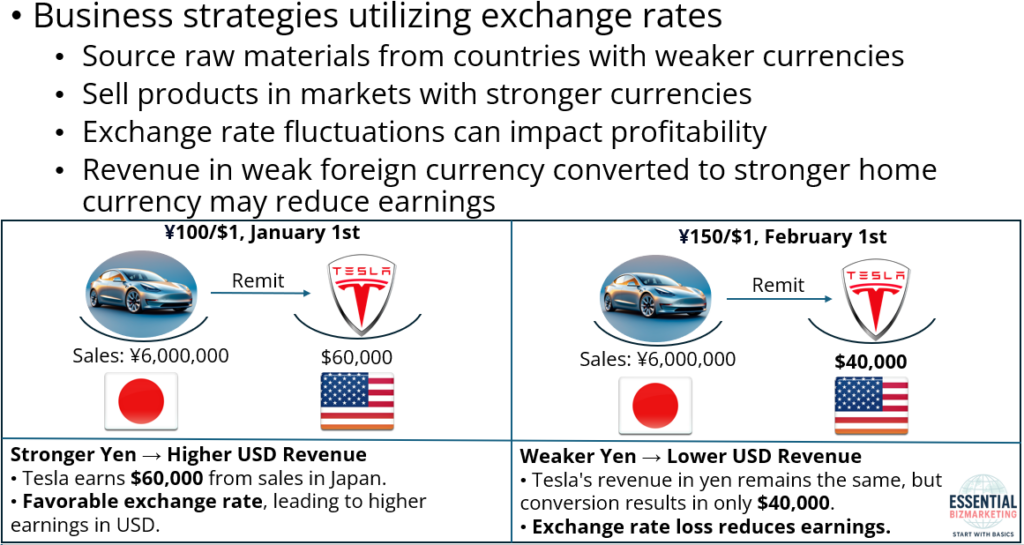

Governments can also influence their currency values intentionally. When a government lowers the value of its currency to boost exports, it is referred to as devaluation.

This image illustrates the impact of currency devaluation on international trade, specifically how a weaker yuan gives Chinese exports a price advantage. Initially, with an exchange rate of 6.5 CNY per USD, both Haier and GE refrigerators are priced equally in the U.S. market at $600. In this situation, competition is based on brand reputation and product quality rather than price, as neither company has a cost advantage.

After the yuan is devalued to 7.5 CNY per USD, the same Haier refrigerator, which still costs 3,900 CNY in China, now translates to only $520 when converted to U.S. dollars. In contrast, the GE refrigerator remains at $600, making Haier the cheaper option. This price reduction increases demand for Haier products in the U.S., resulting in higher Chinese exports and more U.S. imports. The price gap forces GE to compete against a now lower-priced Chinese alternative, intensifying competition for American manufacturers.

This example demonstrates how a weaker currency makes exports more competitive by lowering their price in foreign markets. It also highlights how currency fluctuations directly affect trade balances, with devaluation benefiting export-driven economies like China while creating challenges for domestic producers in importing countries like the United States.

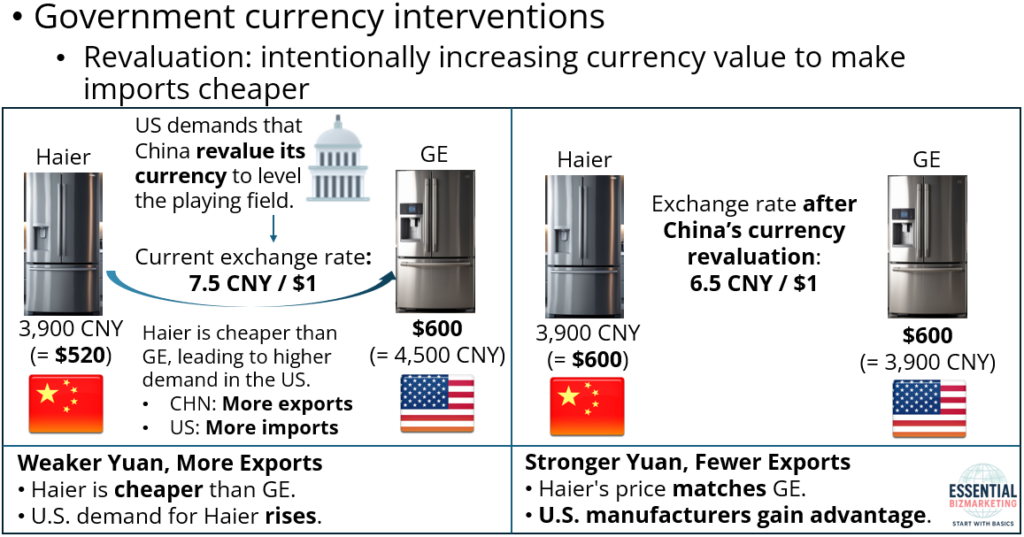

On the other hand, when a government increases the value of its currency, making imports cheaper, it is called revaluation.

This image illustrates how U.S. pressure led China to revalue its currency, impacting trade dynamics between the two countries. Initially, with an exchange rate of 7.5 CNY per USD, Haier refrigerators were priced lower than their American competitor, GE Appliances, making them more attractive to U.S. consumers. As a result, Chinese exports increased while the U.S. imported more Chinese goods, creating an imbalance that American policymakers sought to address.

In response to U.S. demands for a fairer trade environment, China revalued the yuan, strengthening its value to 6.5 CNY per USD. This change caused Haier’s price in the U.S. to rise, eliminating its price advantage over GE. With both refrigerators now costing the same, American consumers no longer had a financial incentive to choose the Chinese product, reducing Chinese exports and benefiting U.S. manufacturers.

This scenario demonstrates how currency appreciation can weaken a country’s export competitiveness, shifting trade advantages in favor of the country with the weaker currency. It also highlights how economic and political pressure from a major trading partner can influence exchange rate policies and global trade dynamics.“

These currency adjustments can have widespread economic effects, influencing trade balances and inflation rates.

2. Factors that Determine Exchange Rates

Exchange rates are influenced by a combination of purchasing power parity (PPP), inflation dynamics, and interest rate differentials. These factors interact across different time horizons, leading to short-term, mid-term, and long-term exchange rate adjustments.

The Law of One Price, Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), and Inflationary Pressures

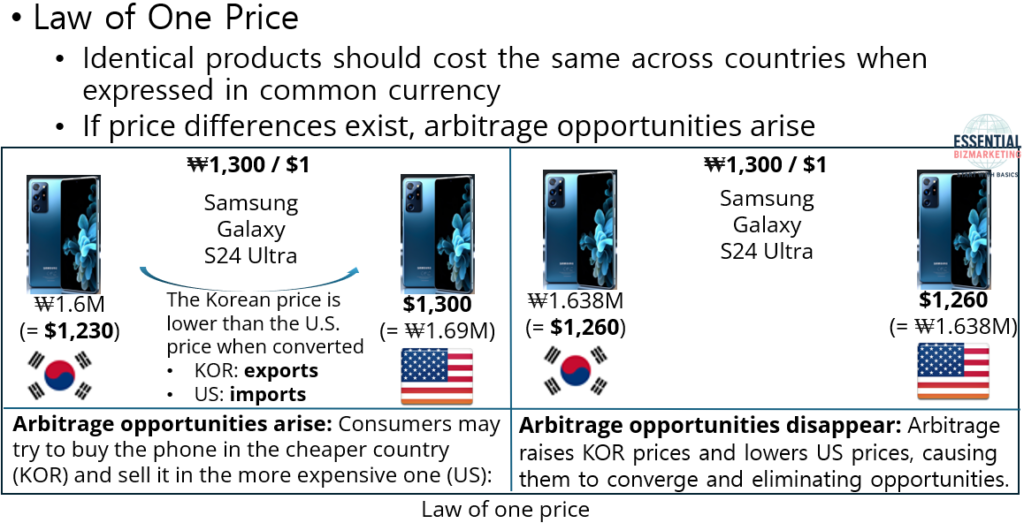

The Law of One Price states that identical goods should cost the same across different countries when expressed in a common currency. Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) extends this idea, predicting that exchange rates should adjust to equalize the purchasing power of different currencies over time.

The image illustrates the Law of One Price, which states that identical products should cost the same across different countries when expressed in a common currency. However, in reality, exchange rate differences often lead to price variations for the same product in different markets.

The example in the image shows the Samsung Galaxy S24 Ultra being sold in both South Korea and the United States under an exchange rate of ₩1,300 per USD. In South Korea, the phone is priced at ₩1.6 million, which, when converted, equals $1,230 in U.S. dollars. In contrast, in the U.S., the phone is sold for $1,300, which, when converted back, is equivalent to ₩1.69 million. This discrepancy creates an arbitrage opportunity, as consumers may attempt to buy the phone at a lower price in South Korea and resell it in the U.S. for a profit. This process leads to increased demand in South Korea, causing local prices to rise, while the additional supply in the U.S. market leads to lower prices there.

Over time, the arbitrage process reduces price discrepancies between the two markets. When prices in both countries adjust and converge, arbitrage opportunities disappear. In the final scenario presented in the image, the price in Korea increases to ₩1.638 million, which, at the same exchange rate, is now equivalent to $1,260 in the U.S. As a result, the price difference narrows, reinforcing the principle that exchange rate movements and market forces drive prices toward equilibrium, aligning with the Law of One Price.

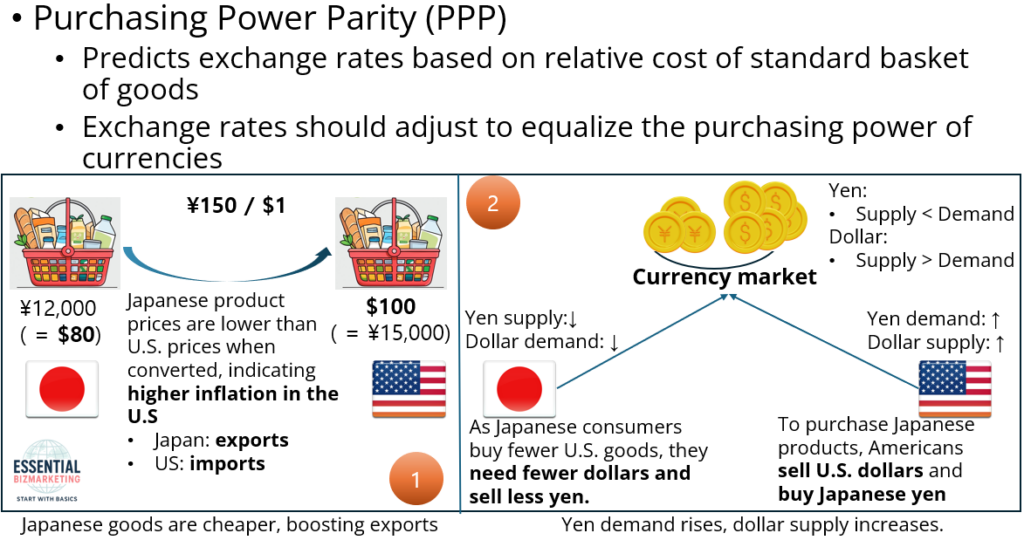

Purchasing power parity (PPP) is a concept that predicts exchange rates based on the relative cost of a standard basket of goods in different countries. If the price of a basket of goods in one country is significantly lower than in another, it indicates that the first country’s currency may be undervalued.

However, deviations from PPP occur due to inflation differences between countries. When one country experiences higher inflation than another, its currency tends to depreciate because rising domestic prices reduce the real purchasing power of money. A country experiencing high inflation will see its goods become more expensive relative to foreign goods. This reduces export competitiveness and increases demand for imports, leading to higher demand for foreign currency and depreciation of the domestic currency.

The images illustrate the concept of Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) and how currency exchange rates adjust due to price differences between countries and inflation differentials. The process begins with a price disparity between Japan and the United States, leading to shifts in supply and demand in the foreign exchange market, which ultimately brings the exchange rate into equilibrium.

In the first stage, the price of a standardized basket of goods is lower in Japan than in the United States when converted using the existing market exchange rate of ¥150 per USD. The basket costs $100 in the U.S. but only ¥12,000 in Japan, which converts to $80. This price difference indicates that Japanese goods are relatively cheaper when priced in U.S. dollars, reflecting higher inflation in the U.S. As a result, American consumers prefer to buy from Japan, leading to an increase in Japanese exports and a decline in U.S. imports.

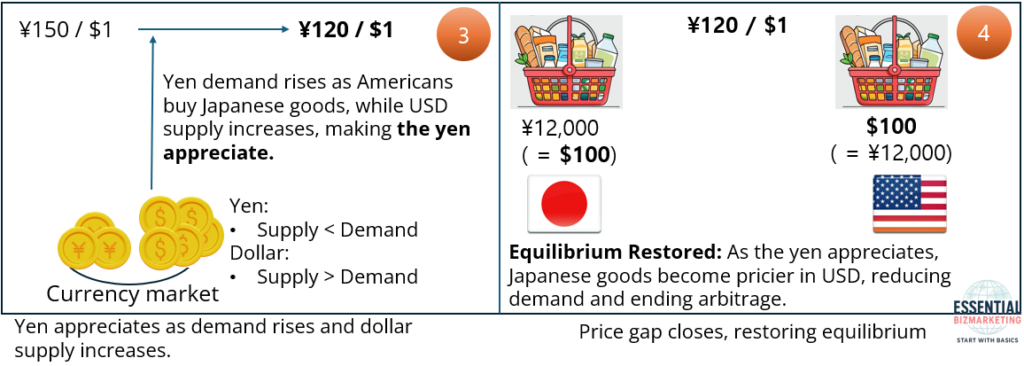

Since more American consumers purchase Japanese goods, they need to exchange U.S. dollars for Japanese yen. This increases demand for yen while raising the supply of U.S. dollars in the foreign exchange market. Simultaneously, Japanese consumers reduce purchases of U.S. goods, leading to lower demand for U.S. dollars and a reduced supply of yen in the market. The combined effect of these currency flows results in the yen appreciating and the U.S. dollar depreciating over time.

As the yen strengthens, the exchange rate moves from ¥150 per USD to ¥120 per USD. This appreciation makes Japanese goods more expensive in dollar terms, reducing demand for imports from Japan. At the same time, the inflation gap between the two countries narrows, and the relative price of U.S. goods becomes more competitive again. As a result, the arbitrage opportunity disappears, and price levels between the two countries become aligned.

In the final stage, the price of the basket in Japan, when converted at the new exchange rate, is now equal to $100, restoring purchasing power parity. This process demonstrates how exchange rate fluctuations adjust to correct price imbalances in international trade while also reflecting inflation differentials between countries.

The Causes of Inflation and Its Effect on Exchange Rates

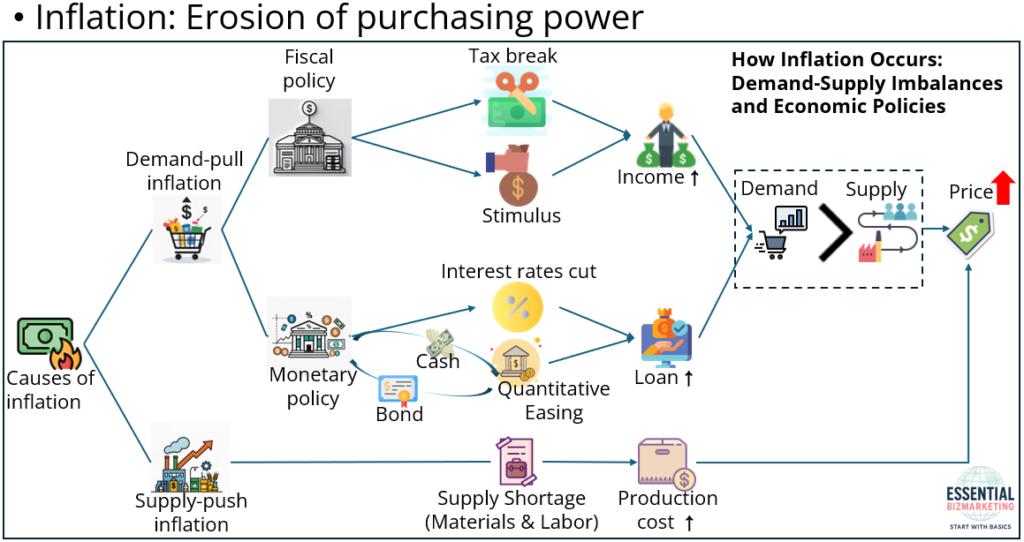

Before examining how inflation affects exchange rates, it is essential to understand why inflation occurs. Inflation arises when there is an imbalance between demand and supply in an economy, which can be triggered by both government policies and market conditions. It can generally be classified into demand-pull inflation and supply-push inflation, both of which contribute to rising price levels and influence currency values.

Factors That Determine Exchange Rates: The Impact of Inflation

Inflation is a crucial factor influencing exchange rates because it reduces the purchasing power of a currency. The diagram illustrates the causes of inflation by distinguishing between demand-pull and supply-push inflation while also explaining how fiscal and monetary policies contribute to inflationary pressures.

Demand-pull inflation occurs when the total demand for goods and services exceeds the economy’s ability to supply them. This can be triggered by both fiscal and monetary policies. In terms of fiscal policy, tax cuts and stimulus packages are often implemented to boost household income. As people have more disposable income, they tend to increase their spending on goods and services. When demand rises faster than supply, businesses struggle to meet consumer needs, which leads to higher prices and, ultimately, inflation.

Monetary policy also plays a significant role in fueling inflation. When central banks lower interest rates, borrowing becomes more affordable, leading to increased consumer and business spending. Additionally, central banks may engage in quantitative easing by purchasing bonds and injecting cash into the financial system. This increases liquidity, allowing banks to offer more loans and businesses to expand investments, which further drives up demand and contributes to inflationary pressures.

In contrast, supply-push inflation occurs when the cost of producing goods and services increases, prompting businesses to raise prices. One common cause is a labor shortage, which forces companies to offer higher wages to attract workers. As labor costs rise, businesses pass those costs on to consumers in the form of higher prices. Similarly, rising costs of raw materials, energy, and transportation increase production expenses, which leads to further price hikes and inflation.

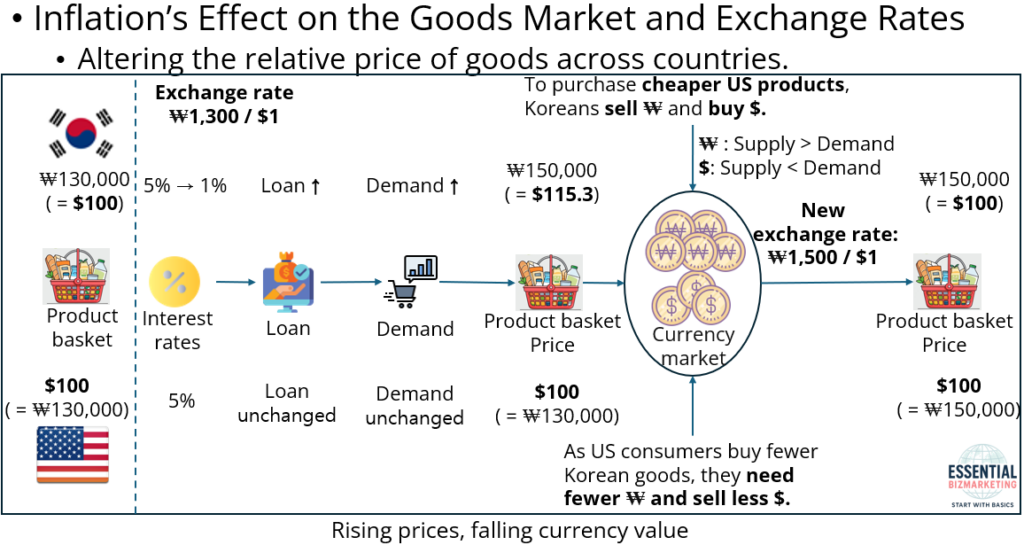

Inflation’s Effect on the Goods Market and Exchange Rates

Inflation influences exchange rates by altering the relative price of goods across countries. A country experiencing high inflation will see its goods become more expensive relative to foreign goods. This reduces export competitiveness and increases demand for imports, leading to higher demand for foreign currency and depreciation of the domestic currency.

This process demonstrates how monetary policy, inflation, and exchange rate adjustments are interconnected, influencing both domestic and international purchasing power. When the central bank lowers interest rates, borrowing becomes easier, leading to increased loans and higher consumption. As a result, demand for goods rises, causing inflation. In this case, the price of Korea’s standard basket of goods increases from ₩130,000 to ₩150,000, while the U.S. basket price remains stable at $100.

As inflation weakens the real value of the Korean won, the exchange rate begins to adjust. Initially, the exchange rate was ₩1,300 per $1, but after inflation, the market responds by pushing the exchange rate up to ₩1,500 per $1. This adjustment reflects the purchasing power shift between the two currencies.

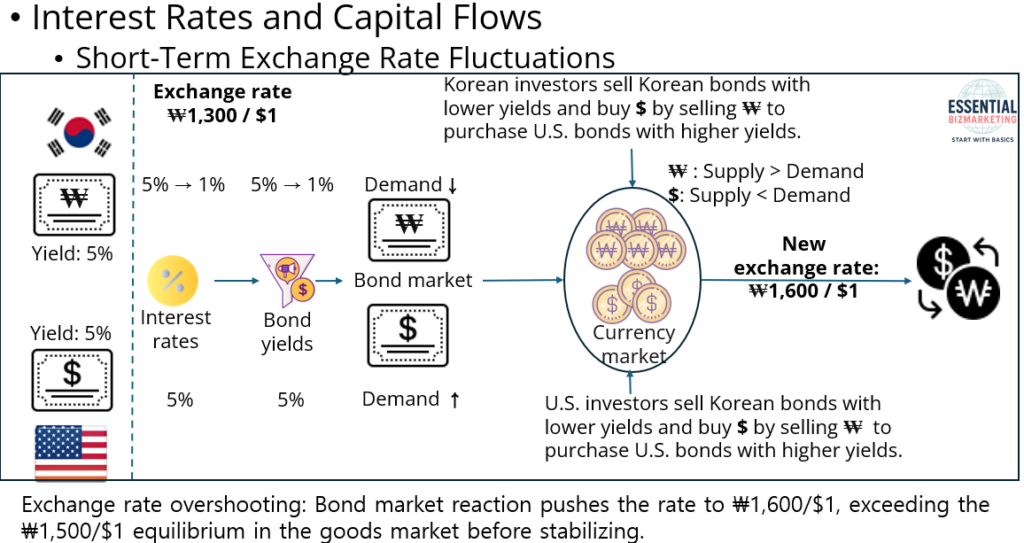

Interest Rates and Capital Flows: Short-Term Exchange Rate Fluctuations

While inflation affects exchange rates gradually, interest rate changes trigger immediate movements in the currency market. When a country’s central bank lowers interest rates, domestic bonds become less attractive, leading to capital outflows as investors seek higher yields abroad. This increases demand for foreign currency, causing an immediate depreciation of the domestic currency.

This diagram illustrates how a change in interest rates influences exchange rates through the bond market. Initially, both South Korea and the United States have an interest rate of 5%, leading to stable investment conditions and an exchange rate of ₩1,300 / $1. However, when the Bank of Korea lowers its interest rate from 5% to 1% to stimulate economic growth, the yield on Korean bonds also declines.

As a result, Korean and foreign investors who previously held Korean bonds find them less attractive due to the lower returns. Seeking higher yields, they start selling Korean bonds and purchasing U.S. bonds, which still offer a 5% return. To buy U.S. bonds, investors need to convert their Korean won into U.S. dollars, increasing the supply of the Korean won in the foreign exchange market while raising the demand for the U.S. dollar.

This shift in capital flows leads to a sharp depreciation of the Korean won, initially causing the exchange rate to overshoot to ₩1,600 per $1 due to the rapid reaction of capital markets. Over time, as the goods market begins to adjust, increased exports and reduced imports help stabilize the exchange rate at ₩1,500 per $1, reflecting the new long-term equilibrium.

This demonstrates how short-term capital flows can cause exchange rate overshooting, whereas long-term trade adjustments drive the currency toward its new equilibrium.

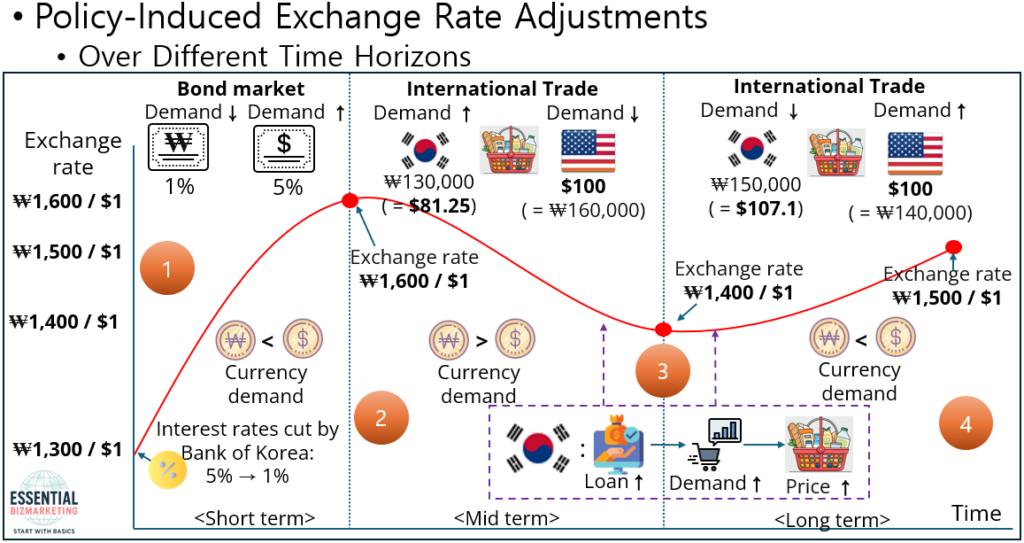

Policy-Induced Exchange Rate Adjustments Over Different Time Horizons

Exchange rates do not adjust instantaneously to policy changes; instead, they evolve over different time horizons as various economic forces come into play. When a central bank alters interest rates or implements expansionary monetary policies, the exchange rate undergoes three distinct phases of adjustment—short-term, mid-term, and long-term—each influenced by different economic mechanisms.

1) Short-Term: Capital Flows and Exchange Rate Overshooting

- Immediately following an interest rate cut, financial markets react swiftly as investors shift capital toward higher-yielding assets abroad.

- This capital outflow leads to a sharp depreciation of the domestic currency, often exceeding its long-run equilibrium level—a phenomenon known as exchange rate overshooting.

- The currency initially weakens far beyond its expected level due to rapid shifts in demand for foreign assets, as seen in the sharp increase from ₩1,300 to ₩1,600 per $1.

2) Mid-Term: Trade Adjustments and Partial Exchange Rate Correction

- As the depreciated currency makes domestic goods cheaper in foreign markets, exports increase while imports decline.

- The rising demand for domestic goods leads to a correction in the exchange rate, with the currency appreciating due to improved trade balances.

- However, this adjustment is not instantaneous—it occurs over months as businesses and consumers gradually respond to relative price changes.

- The exchange rate stabilizes at ₩1,400 per $1, higher than its original level due to inflationary effects accumulating in the domestic economy.

3) Long-Term: Domestic Inflation and Exchange Rate Stabilization

- Over an extended period, increased borrowing and consumption fueled by lower interest rates lead to rising domestic prices.

- Inflation gradually erodes purchasing power, pushing domestic goods’ prices higher.

- As a result, despite earlier trade-driven currency appreciation, the exchange rate moves back up to ₩1,500 per $1, reflecting long-run inflation effects.

Summary:

- Short-term movements are dominated by capital flows and investor sentiment, leading to overshooting.

- Mid-term adjustments occur as trade flows respond to exchange rate changes, leading to a partial correction.

- Long-term stabilization is driven by inflationary pressures, which ultimately dictate the currency’s final equilibrium level.

This framework illustrates how policy-induced exchange rate fluctuations unfold over time, shaped by different economic forces at each stage.

Conclusion

In conclusion, exchange rates are more than just numerical indicators—they are dynamic forces that shape international trade, corporate strategy, and national competitiveness. From price advantages in exports to risks in profit repatriation, businesses must navigate a landscape where even slight currency shifts can alter global outcomes. Moreover, underlying macroeconomic variables like inflation, interest rates, and purchasing power operate across different timeframes, triggering exchange rate movements that ripple through markets. A deep understanding of these interconnected forces empowers firms and policymakers to anticipate challenges and harness opportunities in the ever-evolving global economy.

📚 References

Wild, J. J., & Wild, K. L. (2019). International business: The challenges of globalization (9th ed.). Pearson.

📁 Start exploring the Blog

📘 Or learn more About this site

🧵 Or follow along on X (Twitter)

🔎 Looking for sharp perspectives on global trade and markets?

I recommend @GONOGO_Korea as a resource I trust and regularly learn from.